Safety as 1 Soul: Unveiling Its Invisible Essence

Why safety and Soul behave like an invisible essence, and how to make it visible without corrupting it

Introduction: The paradox we live with

Most organisations today are safer than they have ever been, at least by the metrics we traditionally rely on. Aircraft are technologically sophisticated, procedures are comprehensive, audits are frequent, dashboards are full of reassuring green indicators, and accident rates are historically low. On paper, safety has never looked better.

And yet, when failure occurs, and it inevitably does, it is rarely small, isolated, or surprising in hindsight. Instead, it is systemic, complex, and eerily familiar. The same patterns repeat themselves across industries, geographies, and decades. This creates a deep paradox that many leaders and safety professionals quietly struggle with:

If we are doing so much for safety, why do organisations continue to fail in the same ways?

The instinctive response is to look for gaps in training, compliance, regulation, or oversight. These explanations are comforting because they are actionable and technical. But they are also incomplete. They describe where failures appear, not why they recur.

This essay proposes a more fundamental shift in how we understand safety. It argues that safety does not behave like a technical property or a managerial variable. Instead, it behaves much more like a soul, an invisible, sustaining essence that preserves integrity quietly, and whose absence is noticed only when collapse occurs.

Safety as an object: the mistake we keep repeating

Modern organisations are exceptionally good at managing things that can be seen, counted, and compared. Financial performance, production output, efficiency, utilisation, and growth all lend themselves naturally to measurement. They can be placed on charts, reviewed in meetings, and acted upon with urgency.

Safety, however, does not fit neatly into this worldview. It cannot be touched, stored, or accumulated. Yet we persist in trying to manage it as though it were a tangible asset. We count incidents, track key performance indicators, calculate return on investment, and reward performance. These efforts are rarely malicious; they arise from a genuine desire to control what matters.

The problem is that safety is not something an organisation possesses. It is something an organisation preserves. Like health, trust, or integrity, safety exists as a condition, not an object. You become aware of it most clearly when it begins to erode.

This misunderstanding lies at the heart of many modern safety failures.

The soul analogy: not metaphor, but mechanism

In Indian philosophical traditions, particularly the Upanishadic understanding, the soul (Ātman) is not treated as a mystical ornament added to the body. It is described as the integrating principle that gives coherence, restraint, and awareness to the physical form.

The soul cannot be seen or measured. It cannot be bought, sold, or transferred. And yet, when it is absent, the body, even if anatomically intact, is no longer alive.

Safety plays a strikingly similar role within organisations. Procedures may exist, technology may be advanced, and people may be skilled and well-intentioned. Operations may even continue smoothly for long periods. But when safety, understood as a living awareness of limits and consequences, quietly withdraws, the organisation becomes hollow. Failure then becomes a question of when, not if.

This is why organisations often appear healthy right up to the moment they fail. The indicators we watch are incapable of detecting the loss of the very thing that holds the system together.

What modern safety thinking got right — and what it assumes

It is important to be clear: this perspective does not reject modern safety science. On the contrary, it stands on its shoulders.

Traditional Safety-I thinking brought discipline and structure by defining safety as the absence of accidents. This was an essential starting point. However, it also created a subtle illusion, that silence equates to safety. Much like defining health as the absence of pain, it works only until it doesn’t.

James Reason’s work shifted the conversation decisively away from blaming individuals and towards understanding systemic vulnerability. His Swiss Cheese model revealed how organisations prepare accidents long before the final act. Yet even this powerful framework stops short of explaining why organisations allow defences to thin and warnings to be normalised.

Erik Hollnagel’s Safety-II further advanced the field by recognising that humans are not hazards to be controlled, but resources that enable success under varying conditions. This insight resonates strongly with lived operational reality. But when adaptation is celebrated without restraint, it can quietly legitimise erosion. Success becomes evidence that deviation is acceptable.

High Reliability Organisation theory and Just Culture added valuable insights into mindfulness, fairness, and learning. Still, many organisations have discovered that these ideas are easy to declare and extraordinarily difficult to sustain under pressure. Values collapse most readily when outcomes are at stake.

All of these models implicitly assume that awareness, humility, and ethical restraint will somehow endure. They rarely examine why these qualities fade even in intelligent, well-intentioned organisations.

Loss of salience: the real failure mode

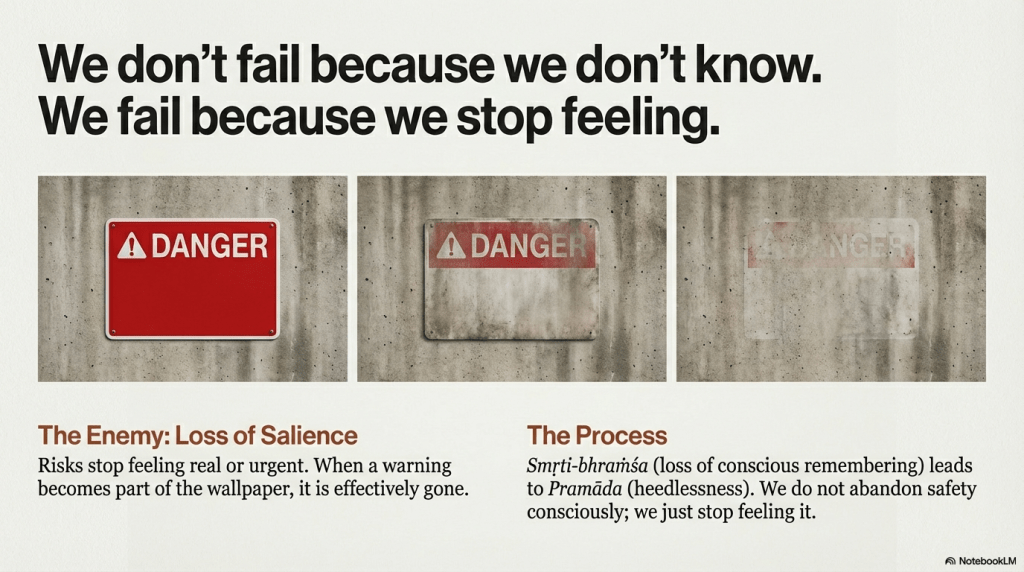

Accidents rarely occur because risks were unknown. More often, they occur because risks lost salience, they stopped feeling real, urgent, or personally relevant.

Salience is what allows something to remain present in awareness. When risk loses salience, shortcuts begin to feel reasonable, warnings feel repetitive, silence feels efficient, and success feels validating. Nothing dramatic announces this shift. That is precisely why it is so dangerous.

Indian philosophy describes this erosion of active remembrance as smṛti-bhraṁśa, the loss of conscious remembering. Its consequence is pramāda — heedlessness. Action continues, but wisdom withdraws.

Organisations do not fail because they consciously abandon safety. They fail because safety slowly stops being felt.

Why safety is never watched like money

Money commands attention because losses are immediate, visible, and personally attributable. A financial shortfall hurts today and demands explanation.

Safety losses behave very differently. They are delayed, invisible, probabilistic, and socially diffused. Early safety erosion often masquerades as success: fewer delays, smoother operations, less friction.

This is why the balance sheet is reviewed obsessively while safety is discussed episodically. One screams for attention; the other whispers. Ignoring safety is not a moral failing, it is a cognitive one.

Making safety visible without turning it into a currency

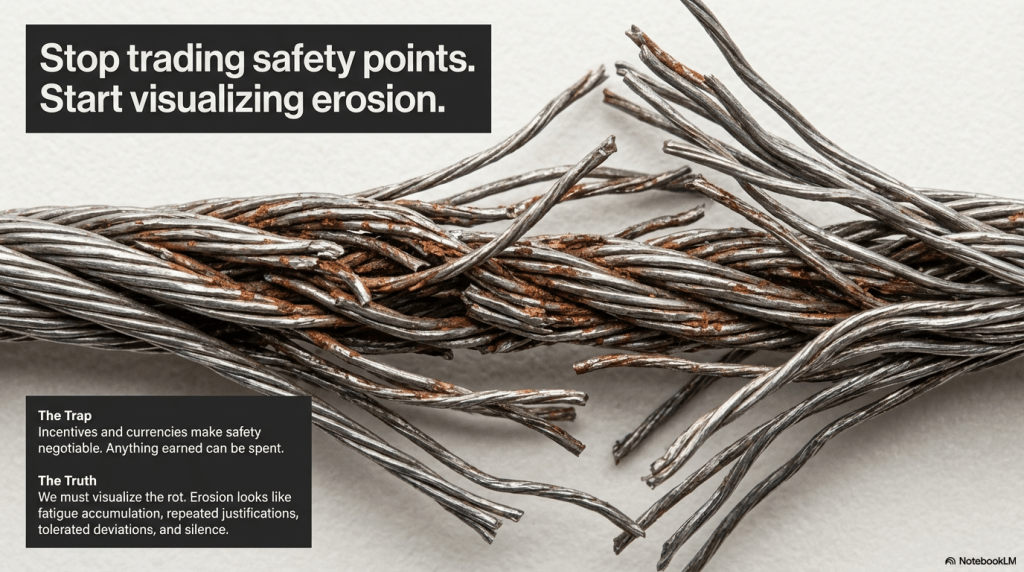

If safety behaves like a soul, the challenge becomes clear: how do we make its presence or absence visible without reducing it to a tradable commodity?

Attempts to create safety points, incentives, or currencies almost always backfire. Anything that can be earned can be spent. Safety must never be negotiable.

What can be made visible is erosion. Fatigue accumulation, repeated justifications, tolerated deviations, unspoken concerns, and success-driven arrogance all signal the quiet depletion of safety margin.

This is accounting, not trading.

The safety balance sheet: seeing what really matters

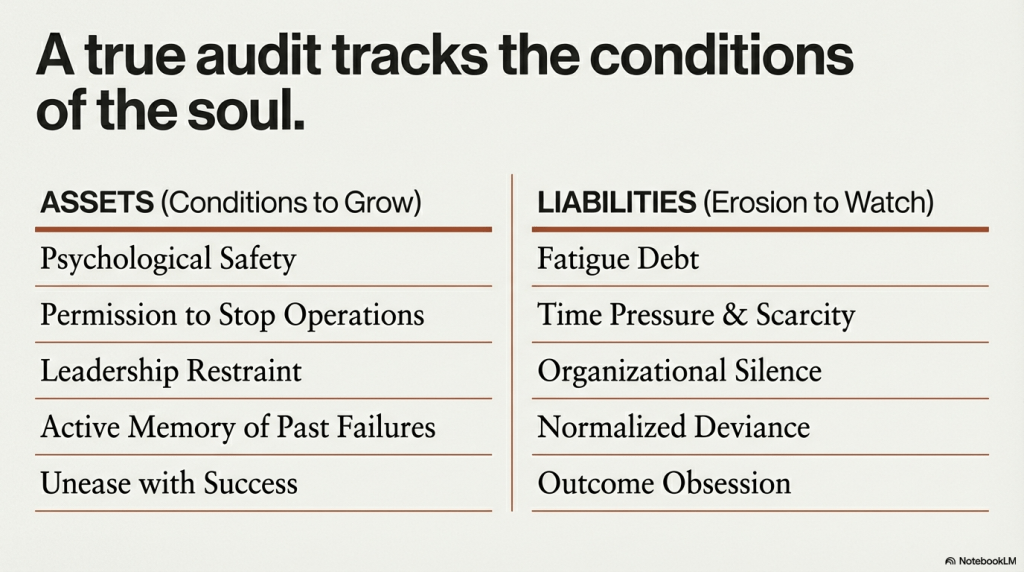

A meaningful safety balance sheet does not count accidents. It tracks conditions.

Assets include psychological safety, permission to stop, leadership restraint, learning from near-misses, and remembered accidents. Liabilities include fatigue debt, time pressure, silence, normalised deviance, and outcome obsession.

When liabilities grow and no one feels uneasy, safety is already leaving.

Individuals fail suddenly; organisations fail slowly

At the sharp end, individuals fail under stress, fatigue, surprise, and cognitive lock-up. These failures are sudden and visible.

Organisations fail through gradual drift, success reinforcement, muted dissent, and ritualised compliance. These failures are slow and largely invisible.

By the time an accident occurs, organisational safety has often been absent for years.

Awareness and visibility: not opposites, but partners

Awareness is essential, but fragile. It collapses under hierarchy, fatigue, time pressure, and conformity. Organisations that rely on awareness alone are relying on hope.

Visibility, thoughtfully designed, allows awareness to survive stress, turnover, and time. Awareness is the source; visibility is the carrier.

Safety as conscience, not compliance

Ultimately, safety is closer to conscience than to compliance. It restrains when nothing external stops us. It whispers when success tempts us. It asks uncomfortable questions when numbers look good.

When safety becomes paperwork, it loses this function.

Conclusion: What changes when safety is seen this way

Seeing safety as a soul reframes everything. Accidents become symptoms, not surprises. Leaders become custodians of integrity rather than enforcers of rules. Visibility focuses on erosion, not outcomes. Success is treated with curiosity, not complacency.

This perspective does not reject modern safety science. It completes it.

Safety is not what keeps accidents away. Safety is what keeps organisations whole.

When that wholeness is lost, the collapse is rarely quiet — even though the loss itself was.

Discover more from Safety Matters Foundation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply