Jumpstart Blame Narratives: Silence Becomes a Story in Aviation AI171

In the hours after an aviation accident, the world wants answers immediately. Families want clarity. Newsrooms want a storyline. Social media wants someone to hold responsible. But accident investigation is not built for speed—it is built for truth. That mismatch between public urgency and technical reality creates an information vacuum. And in aviation, vacuums get filled fast.

Too often, what fills the space is not evidence but certainty theatre: confident talk, selective “sources,” dramatic cockpit narratives, and premature conclusions—frequently culminating in the most convenient headline of all: pilot error.

ICAO’s Doc 10053 acknowledges this reality directly. It recognises that interaction between media and the accident investigation authority is not a “nice-to-have.” It is a safety-critical function, because poor communication can trigger misinformation, distort public understanding, harm trust, and, in the worst cases, pressure the system toward scapegoating rather than learning.

This article examines how speculation and false media narratives—especially pilot-blame narratives—could have been significantly reduced if an AAIB-style authority applied Doc 10053’s guidance with discipline in a case like AI171. This is not a comment on accident causation. It is a comment on communication as a safety barrier.

The first 48 hours: when truth is slow and narrative is instant

Doc 10053’s media section highlights that accident investigations attract intense media attention and that public interest peaks early. The implication is simple: if the official system does not provide a steady stream of verified, factual information, others will provide something else.

In practice, the first 12 to 48 hours after an event are where narratives are formed and emotionally “locked in.” The pattern is predictable:

- A small set of unverified details circulates.

- Commentators turn details into interpretations.

- Interpretations turn into certainty.

- Certainty turns into blame.

- Blame becomes the story that everything else must fit.

Once an early story forms—especially a “pilot did X” story—it becomes an anchor. Later evidence may arrive, but the correction is fighting an uphill cognitive battle. Humans remember first impressions. We defend the first narrative we emotionally accepted. We share the dramatic version, not the accurate version.

That is why Doc 10053 places responsibility on investigation authorities to be robust enough to withstand media pressure—and organised enough to prevent the media cycle from turning into a parallel “rapid investigation.”

Why pilot-blame becomes the default

To understand why Doc 10053 matters, we must understand why pilot-blame is so attractive in the public arena.

Aviation accidents are rarely the result of a single failure. They involve complex interactions between machine, environment, training, procedures, maintenance, regulation, organisational pressures, and human performance under stress. But complexity is not comforting. Complexity is not television-friendly. Complexity doesn’t produce instant moral closure.

A single human culprit does.

Pilot-blame narratives are powered by familiar cognitive biases:

- Single-cause hunger: “Tell me the one reason.”

- Hindsight bias: “It was obvious what they should have done.”

- Outcome bias: “If the outcome was bad, the decision must have been bad.”

- Fundamental attribution error: “It happened because of who they are, not what they faced.”

- Story bias: we prefer a neat plot with a protagonist and a mistake.

None of these biases care about recorder downloads, metallurgy, flight data correlation, or systems analysis. They care about emotional resolution. And that is precisely why an investigation authority must protect the learning space—before the blame space consumes it.

Doc 10053’s central insight: don’t let the media do “rapid analysis” in a vacuum

The Doc 10053 guidance you shared essentially warns of two things:

- Media will report quickly, often with incomplete facts.

- Incompleteness creates error—and error becomes narrative.

It also suggests a remedy: the accident investigation authority should be capable of ensuring accurate reporting by disclosing as much information as possible, consistent with protecting the investigation—supported by a policy that encourages correct reporting.

This is not about “controlling” the press. It is about preventing misinformation from becoming a public verdict.

The Doc 10053 playbook: communication as a safety barrier

Below is a practical, Doc 10053-aligned strategy that can dramatically reduce speculation and pilot-blame.

1) Fill the vacuum early—without speculating

The first public statement is not meant to solve the accident. It is meant to stabilise the information environment.

A Doc 10053-style first statement (ideally within hours) should include:

- confirmed basics (time, location, aircraft/operator as appropriate, response actions),

- what is being done (site security, evidence protection, coordination with stakeholders),

- a firm boundary: no cause conclusions at this stage,

- a commitment to cadence: “Next update at ___ local time.”

This does a powerful thing: it tells the public that the investigation is real, organised, and progressing—and it reduces the perceived need for rumor.

2) One spokesperson: technically competent, trained, and consistent

Doc 10053 supports the idea that interaction with the media should be handled by a designated spokesperson—ideally part of or closely linked to the investigation authority—technically competent and trained.

Why does this matter?

Because multiple voices create contradictions. Contradictions are interpreted as incompetence or deception. And once the public suspects deception, they become even more susceptible to dramatic theories.

A calm, consistent spokesperson with a fixed update schedule reduces anxiety and prevents the press from hunting “alternative sources.”

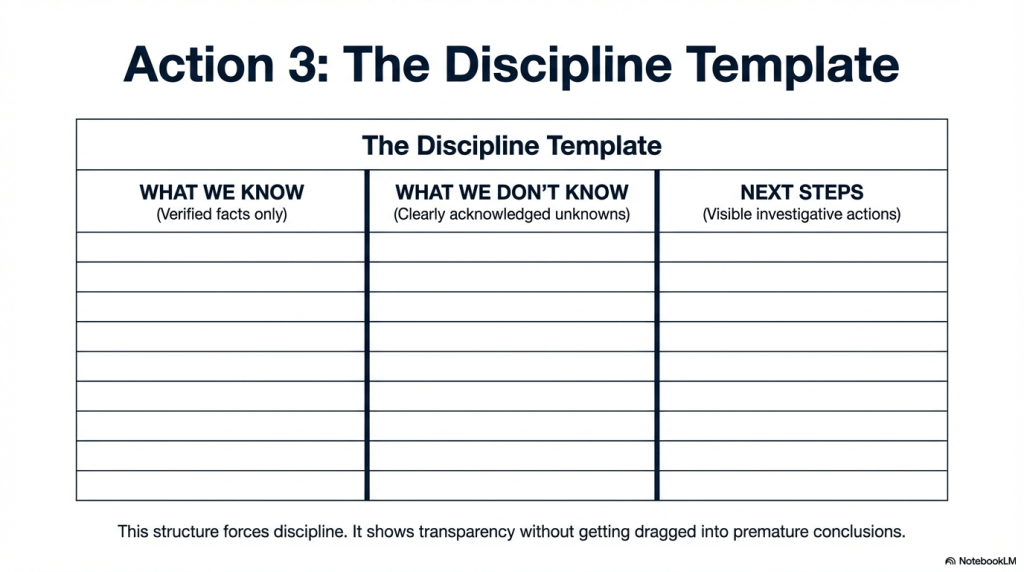

3) Use the structure: “What we know / What we don’t know / What we are doing next”

This simple template prevents accidental overreach.

- What we know: verified facts only.

- What we don’t know: openly acknowledged unknowns.

- What we are doing next: visible steps—recorder download, lab analysis, interviews, data correlation.

This structure helps media report responsibly because it gives them clean, publishable content without inventing interpretation.

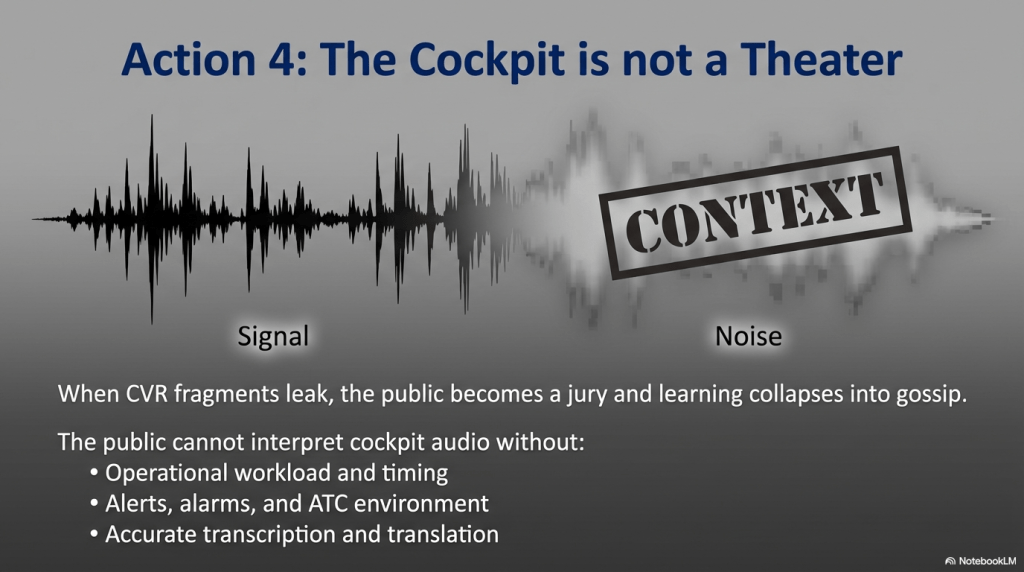

4) Protect sensitive evidence—especially CVR

Doc 10053 emphasises protection of sensitive records such as cockpit voice recordings. This is critical.

A CVR is not a public entertainment product. It is not a “truth clip.” Without context, it is easily misunderstood and weaponised. A single phrase—misheard, mistranslated, or stripped of timing—can become a character assassination tool.

Once that happens, pilot-blame becomes unstoppable because the public thinks they have “heard the truth.”

A Doc 10053 approach is clear: protect such data, avoid partial disclosure, and resist the temptation to “clarify” rumors by confirming fragments. You don’t correct rumor with partial evidence; you correct it with disciplined process and verified releases.

5) Rumor-control without debate

A practical extension of Doc 10053 is a “rumor control” page or section:

- “We are aware of claims circulating about X.”

- “This is not verified.”

- “Please rely on official updates.”

- “We will confirm when evidence supports it.”

This is calm, factual, and non-combative. It does not amplify rumor by arguing; it simply marks boundaries.

The AI171 lesson: how pilot-blame narratives gain traction—and how to slow them

Again, without commenting on causation, here is how pilot-blame narratives usually form:

- Minimal early information from the authority.

- Long gaps between official updates.

- Inconsistent or multi-source messaging.

- “Leaks” or anonymous claims about cockpit actions or conversations.

- Commentators filling airtime with confident theories.

- The public adopting a villain-based explanation.

A Doc 10053-aligned strategy would reduce the space for all of that. Not by defending pilots. By defending the investigation process.

And that matters because investigation is not just technical work—it is also trust work. If the public sees the authority as credible and steady, speculative narratives struggle to survive.

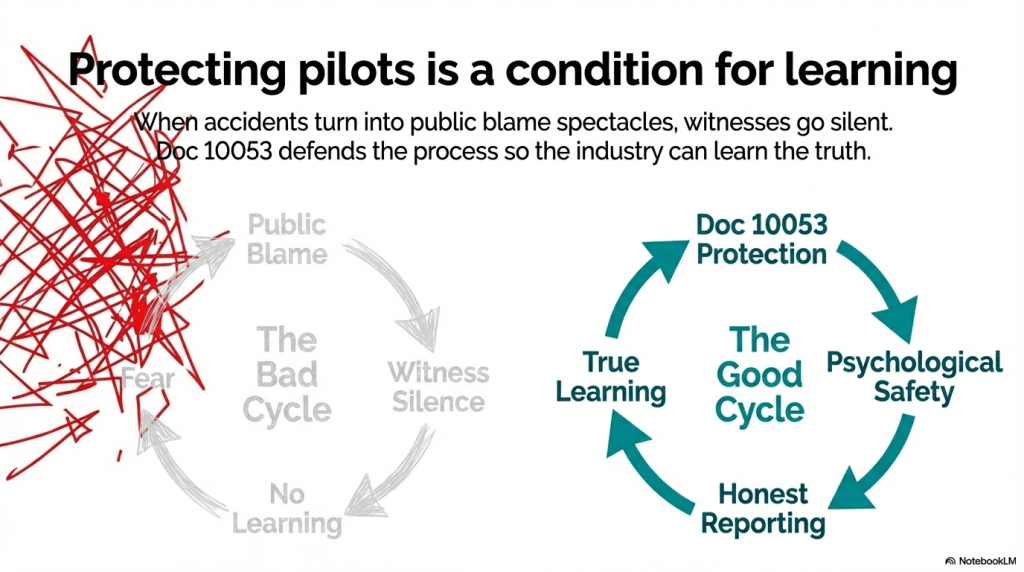

Safety culture: premature blame damages learning

Aviation safety depends on reporting, openness, and psychological safety. When accidents become public blame spectacles:

- individuals become defensive,

- organisations become legalistic,

- witnesses become cautious,

- reporting declines,

- learning becomes performative.

Just culture is not softness. It is an engineering requirement for truth: without it, you don’t get honest data.

Doc 10053’s media guidance is, in effect, just culture’s external shield: it prevents the public arena from turning the investigation into a trial before facts exist.

An Indian lens: rajas and tamas in the media storm, sattva in the investigation

Indian wisdom adds a deeper layer to why this matters.

The breaking-news ecosystem amplifies rajas (agitation, urgency, emotional churn) and tamas (simplification, inertia, scapegoating). Together they create the perfect environment for blame.

A credible investigation must cultivate sattva—clarity, steadiness, truthfulness.

Doc 10053 is a sattvic discipline in institutional form:

- measured speech,

- verified facts,

- patient process,

- ethical protection of sensitive evidence,

- non-attachment to public pressure.

This is also karma-yoga: do the duty of truth-seeking without attachment to applause, outrage, or immediate closure.

What investigation authorities can implement immediately (Doc 10053 aligned)

Within 0–6 hours

- single factual statement,

- purpose: prevention, not blame,

- what’s being done now,

- next update time.

First week

- daily fixed-time updates,

- same spokesperson,

- “know / don’t know / next steps” structure,

- rumor-control section.

Evidence protection

- no CVR fragments,

- no interpretive language,

- no anonymous “technical hints.”

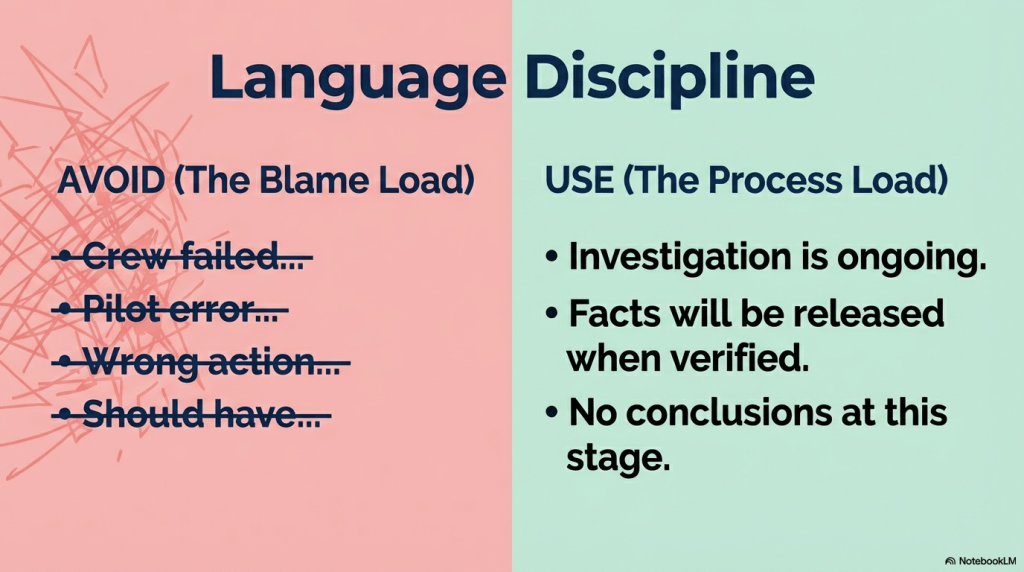

Language discipline

Avoid early phrases that imply culpability (“crew failed,” “pilot error,” “wrong action”).

Use process language (“investigation ongoing,” “facts will be released when verified,” “no conclusions at this stage”).

Closing thought: silence is not neutral

Silence after an accident is not neutrality. It is a vacuum. And vacuums don’t stay empty.

Doc 10053 exists because aviation learned—repeatedly—that misinformation is not just reputational harm. It is a safety hazard. It damages trust, discourages reporting, and pushes the system toward blame instead of learning.

If we want safer skies, we must protect investigations from becoming public entertainment—and protect pilots from becoming convenient villains before evidence is even assembled.

Discover more from Safety Matters Foundation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply