Deputation Nation: How India Is Turning Aviation Safety Into a Temporary Arrangement

India wants to be an aviation superpower. Bigger fleets, busier skies, more airports, more pride. But here is the uncomfortable truth: you can’t build a superpower on temporary safety.

And yet, that is exactly what we are signalling when core aviation safety functions—especially accident investigation—are treated like roles that can be filled “for now,” by whoever is available, on short-term arrangements, rotating doors, and borrowed time.

Aviation safety does not collapse in one dramatic moment. It decays. Quietly. Administratively. Systemically. Then it shows up as a headline.

The question is not whether India is growing. The question is: where are we headed if our institutions are not growing with the same seriousness as our traffic?

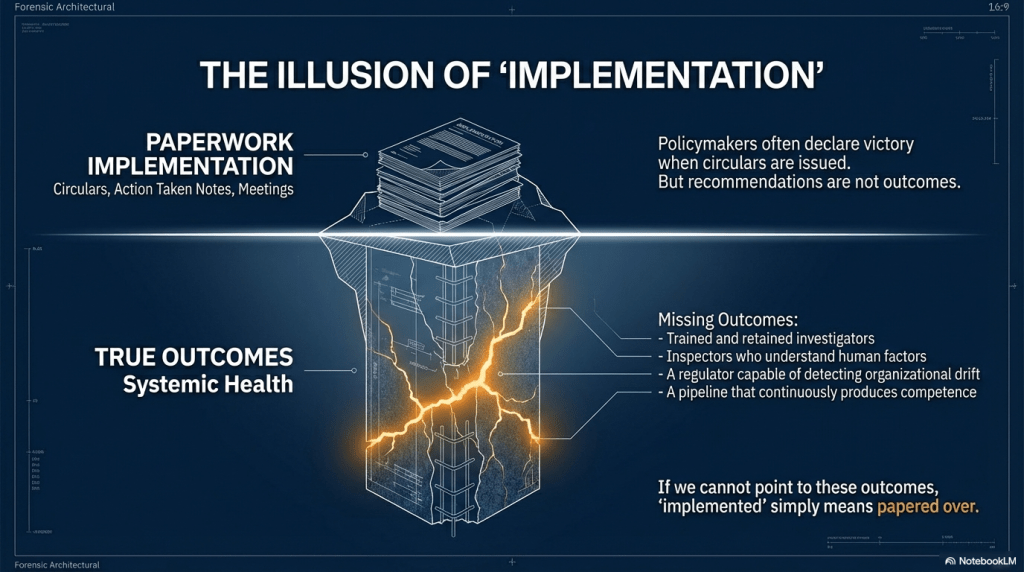

The Illusion of “Implementation”

We have a national habit: when a tragedy happens, we respond with a flurry of circulars, meetings, audits, and “action taken” notes. Then we declare victory. We say: recommendations implemented, lessons learned, systems improved.

But here is what policy makers must confront:

Recommendations are not outcomes.

Outcomes are:

- trained and retained investigators,

- inspectors who understand human factors and systems thinking,

- a regulator capable of detecting organisational drift,

- an investigation process protected from blame-driven misuse,

- a pipeline that continuously produces competence.

If we cannot point to those outcomes, then “implemented” often means just one thing: papered over.

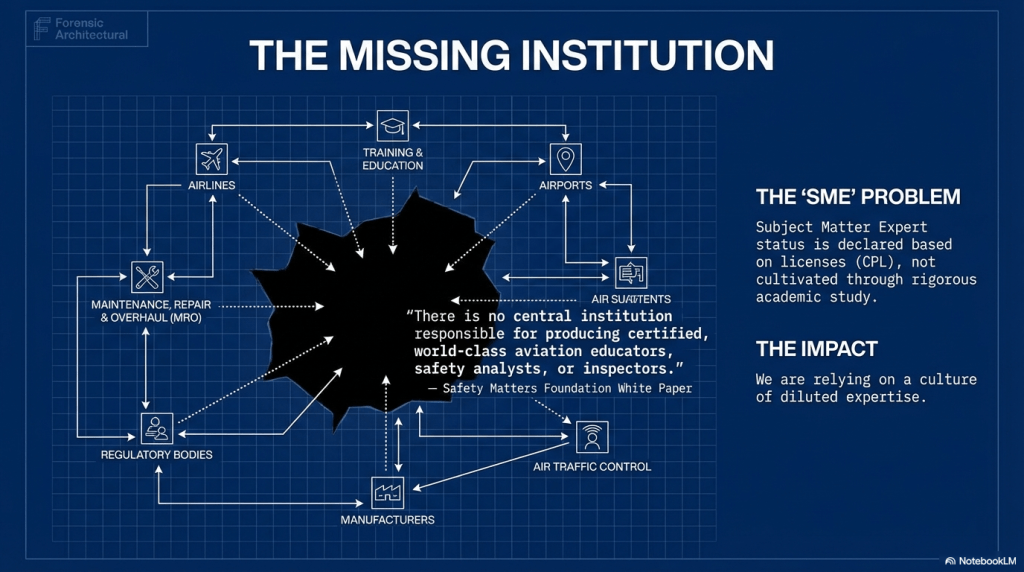

The White Paper That Should Have Shaken the System

Days before the AI171 accident, Safety Matters Foundation submitted a white paper that reads like a warning flare. Not a philosophical essay. A blunt institutional diagnosis.

It begins with a line that should alarm any serious government:

“There is no central institution responsible for producing certified, world-class aviation educators, safety analysts, or inspectors.”

Let that sink in.

No central institution producing educators, safety analysts, or inspectors.

In a sector that markets itself as “world-class,” this is the equivalent of saying:

we are scaling the sky, but not scaling the spine.

The white paper also calls out a culture of diluted expertise:

“Anyone with a CPL and a short course is labeled an ‘SME’ (Subject Matter Expert).”

This is not a personal insult. It is a structural critique: safety-critical competence is being declared rather than cultivated.

And then comes the line that should end all complacency:

“Aviation’s disregard for structured teacher training is leading to inconsistent outcomes and, in some cases, fatal errors.”

This is not “one more recommendation.” This is the blueprint of systemic risk: weak pipelines produce weak outcomes.

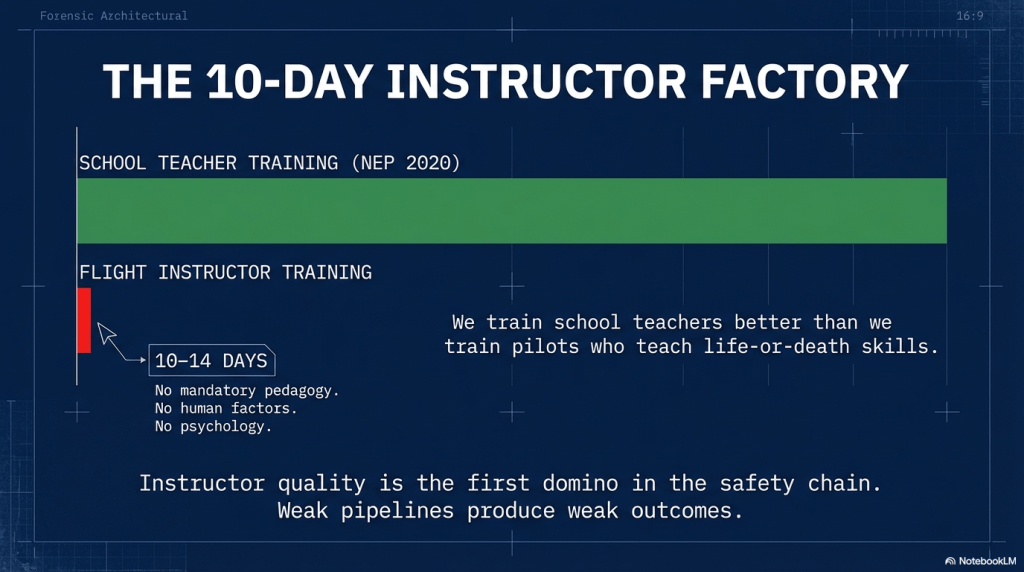

The 10–14 Day Instructor Factory

The white paper points out that:

“Flight instructor training typically lasts only 10–14 days.”

And:

“There is no mandatory pedagogy, human factors, or psychology training.”

Now compare that with NEP 2020, where even school teachers undergo structured training and certification. The white paper makes that contrast explicitly.

So India expects more training discipline for classroom teachers than for aviation instructors who shape cockpit behaviour under stress.

That should embarrass the system into reform. Instead, we keep pretending it’s a minor detail.

It isn’t. Instructor quality is not a “training department issue.”

It is the first domino in the safety chain.

Audits That Exist to “Resume Operations”

The white paper delivers an indictment of oversight culture that many insiders recognise but few will say aloud:

“Flight school audits in India are reactionary and often superficial.”

Then it cites an accident summary line that is almost unbelievable:

“Audit of the flight school was conducted to enable it to resume operations.”

That sentence is not just bad optics. It reveals the purpose of the audit: not diagnosis, not risk reduction—permissioning.

When audits become “restart certificates,” oversight turns into a ritual. And rituals don’t prevent accidents. Systems do.

And then comes the capability gap inside the regulator:

“many DGCA inspectors lack training in human factors, organizational behavior, or system safety analysis.”

This is how institutional drift becomes normal. The system starts focusing on what is easy to check—documents, signatures, tick-box compliance—while missing what actually kills: fatigue, cognitive lock-up, training scars, normalisation of deviance, authority gradients, organisational pressure.

The Most Dangerous Boundary: When Safety Investigation Becomes a Weapon

There is another part of the white paper that is critical for policy:

It argues that accident investigation outcomes are being treated as prosecutorial verdicts, and that police action often begins automatically, with AAIB (Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau) reports treated as “final evidence.”

When this happens, a Just Culture dies. Quietly. Completely.

Because once people believe that honest disclosure will become evidence against them, they do what humans always do under threat: they protect themselves first. They report less. They speak less. They admit less. They hide more.

Safety becomes blind.

A supporting letter to the Law Secretary underscores this clearly: AAIB reports are meant for prevention, not blame, and premature use in criminal or civil proceedings risks diverting them from their purpose.

This is not a “legal nuance.” It is the oxygen of learning.

Now Connect It to the Vacancy Circulars

This is where the official vacancy notices matter—not because staffing is sexy, but because staffing is destiny. The circulars for key investigator positions in the AAIB are not mere administrative documents; they are a confession of institutional strategy.

Exhibit A – The Verbatim Evidence:

A recent circular for an “Investigator (Operations)” post states:

“Appointment will be on deputation (including short-term contract)… for an initial period of three years extendable as per requirement.”

Another for a “Senior Investigator (Airworthiness)” echoes:

“The post is to be filled by deputation… period of deputation shall be three years.”

If core investigation capacity is repeatedly built on deputation and short-term contracts, the message is:

- investigation is a posting, not a profession;

- continuity is optional;

- institutional memory is expendable;

- independence can be compromised by dual loyalties;

- capability will be rebuilt from scratch every few years.

And that is fatal because the system’s greatest safety advantage is cumulative learning over time.

You cannot do cumulative learning with a revolving door.

Aviation does not forgive revolving doors.

Where Are We Headed If We Keep Doing This?

If we continue on this path—rapid growth, weak pipelines, superficial audits, and short-term staffing of safety institutions—we are headed toward a future where:

- Competence becomes uneven at scale.

We will have brilliant professionals and fragile ones—mixed into the same system. - Regulation becomes a paperwork enterprise.

Compliance will improve. Real safety will not keep pace. - Investigation becomes less trusted.

People will fear it. And what people fear, they don’t feed with truth. - The same lessons will be relearned at the cost of lives.

Not because we didn’t know. Because we refused to institutionalise what we knew.

That is what institutional negligence looks like: not ignorance—refusal to build.

What Must Change (In Plain Policy Language)

If India wants aviation greatness without gambling with lives, it must do three hard things:

1) Build Permanent Pipelines, Not Temporary Staffing

Create career cadres for investigators, inspectors, safety analysts, and educators. Deputation can supplement. It cannot be the model. The circulars must shift from “deputation for three years” to “permanent specialist cadre.”

2) Professionalise Aviation Instruction

Instructor training cannot remain a short-course tick-box. The white paper’s call for pedagogy + human factors + facilitation is not optional; it is overdue. Align it with the NEP 2020 philosophy: teaching is a profession.

3) Firewall Safety Investigation From Blame-Driven Misuse

If safety outputs are treated as prosecutorial evidence, reporting culture collapses. This boundary must be clarified, codified, and enforced, as the white paper urges. The AAIB’s independence must be sacrosanct.

Conclusion: A Nation Cannot Outsource Its Safety Backbone

India can buy aircraft. It can build terminals. It can announce growth.

But it cannot buy trust in safety institutions.

Trust is earned through:

- permanence,

- competence,

- independence,

- and the courage to learn without fear.

If we keep staffing safety like it is temporary—as the vacancy circulars prove we do—then risk becomes permanent.

And one day, when the alignment of small institutional weaknesses becomes a big event, we will again say: “We will implement recommendations.”

No.

This time, we must say something harder:

We will build institutions.

Because only institutions outlive accidents. Only institutions prevent recurrence. Only institutions convert tragedy into lasting safety.

Anything else is theatre.

Discover more from Safety Matters Foundation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply