🛑 HOW SEAT 11A SURVIVED — AND WHY DOZENS OTHERS DIDN’T: THE SHOCKING TRUTH ABOUT AIR CRASH SURVIVABILITY

“One seat. One survivor. 241 dead. But science shows over 50 people could have survived — if the seatbelt didn’t betray them.”

✈️ AI171: A Survivable Crash — with 241 Deaths

On 12 June 2025, Air India flight AI171, a Boeing 787 Dreamliner, took off from Ahmedabad, India. Shortly after takeoff, both engines lost thrust.

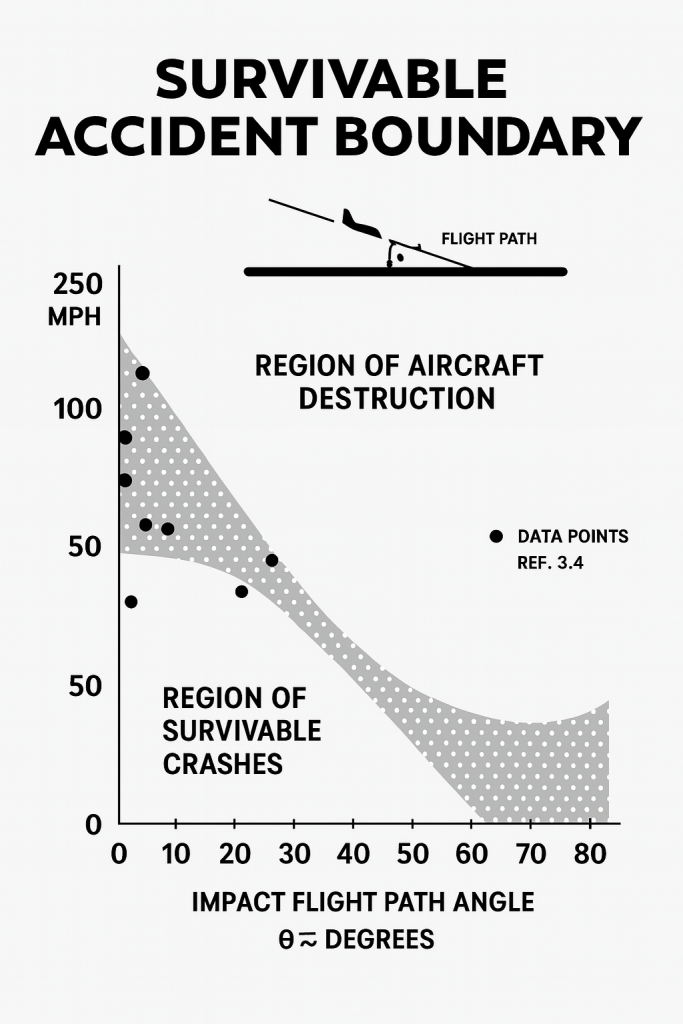

The aircraft glided for 35 seconds in a nose-up attitude—a profile known in crash science to be partially survivable. Then, the tail struck a building first, followed by the fuselage, and a fire erupted.

Out of 242 occupants, 241 died.

Only one man lived.

He was seated at 11A — near the aircraft’s strongest structural zone.

The only way he could have survived, as per research, was by not wearing his seatbelt or if his seatbelt failed.

🧠 SCIENCE, NOT MIRACLE: WHY 11A SURVIVED

🔩 1. Seat 11A: The Wing Root Advantage

Seat 11A is located near the wing root — the most structurally reinforced part of a commercial aircraft, housing the main spars. This region absorbs and disperses energy more efficiently in a crash.

According to the crashworthiness model “CREEP” (Grierson & Jones, 2001):

- C – Container: Space remained intact.

- R – Restraint: Freedom of motion prevented internal injury.

- E – Energy absorption: Tail and mid-section absorbed vertical load.

- E – Environment: Fire reached late.

- P – Post-crash: Exit routes may have remained momentarily accessible.

💺 THE SILENT KILLER: SEATBELT SYNDROME

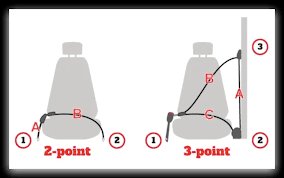

Ironically, the standard 2-point lap belt, designed to protect passengers, may have contributed to fatalities.

⚠️ What is Seatbelt Syndrome?

A large percentage of deaths in commercial airline crashes are caused by the limbs flailing around the seat belt.

Seatbelt syndrome refers to the set of internal injuries caused by the restraining force of a lap belt during deceleration:

- Spinal fractures

- Abdominal perforations

- Mesenteric tears

- Organ lacerations

“Lap-only restraints prevent the pelvis from moving forward but allow the torso to violently bend, crushing internal organs”

— Tejada (2005); Li & Baker (1997)

In contrast, 3-point shoulder harnesses:

- Reduce spinal flexion

- Prevent abdominal compression

- Preserve consciousness — key to self-evacuation

🔗 The Seatbelt Paradox: When Not Wearing One Might Help

Here comes the controversial part: it is believed the survivor was not wearing a seatbelt or the seatbelt failed easily.

Usually, that would be dangerous, but in 99% of cases. But in low-speed, tail-first, nose-up crashes, the vertical energy is absorbed by the aircraft’s undercarriage or tail. The forward motion is slower.

In such cases, a lap belt — which only restrains the pelvis — can cause severe injuries:

- Seatbelt syndrome: damage to intestines, spine, or abdominal vessels

- Spinal compression from torso whiplash, as the body pivots over the lap belt

- Torso injuries due to belt fixation while the upper body violently flails

But if you’re unbelted, your body moves with the cabin rather than against it. If the fuselage tears or deforms, you might be thrown clear of a collapsing seat or ceiling.

🔍 The evidence: The 11A survivor had facial injuries, not abdominal or spinal ones. This is consistent with unrestrained forward flailing, not compression injuries from a lap belt.

The lone survivor at 11A could have survived by not wearing his seatbelt, which may have allowed his body to move with the aircraft instead of absorbing direct force.

✅ How Clear Forward Space Helps in a Crash

No Seat Back to Slam Into

The front seat becomes the first impact point during a crash in most rows. The torso and head are violently thrown forward into the hard back of the seat ahead, often causing:

- Skull fractures

- Facial injuries

- Thoracic trauma

- Spinal damage

🔹 Seat 11A had at least 6 feet of open space ahead due to the emergency exit configuration.

🔸 Result: No immediate surface for blunt trauma, reducing force on the upper body.

✅ Reduced Risk of Seatbelt Syndrome

In a lap-belt-only system (2-point belt), the torso pivots forward while the hips are held back, creating a jackknife motion. This results in:

- Bowel perforation

- Lumbar spine fracture

- Mesenteric tears

💡 But without a sudden stop from a front seat, and possibly no belt worn, the survivor avoided this high-tension compression, reducing or eliminating seatbelt syndrome injuries.

✅ Extra Space = More Deceleration Time

Physics tells us:

🕒 More distance = more time to decelerate

🛑 That reduces peak forces on the body.

Think of it like crumple zones in cars — extra space ahead allowed his body to slow down over distance, not stop instantly.

✅ Supporting Research

The FAA and crash dynamics studies show:

“Passengers seated at bulkhead or exit rows experience different deceleration forces due to absence of seat backs ahead. Injuries in these zones tend to be lower if no rigid barrier is present.”

(Source: FAA CAMI, Crashworthiness Studies)

🔥 THE REAL KILLER: POST-IMPACT FIRE

According to Safety Science (Ekman & Debacker, 2018) and multiple ICAO reports:

- Survivability is highest in tail-first, low-speed crashes.

- However, fire and smoke become the dominant killers.

“Occupants who survive the crash often perish due to toxic smoke, blocked exits, and inability to evacuate due to seatbelt or spinal injury.”

— NTSB (2001); Li et al. (2008)

In AI171:

- Survivable impact for mid-cabin and tail passengers

- Fire engulfed the cabin before most could unbuckle and exit

- Evidence: most injuries were not blunt trauma, but burn-related

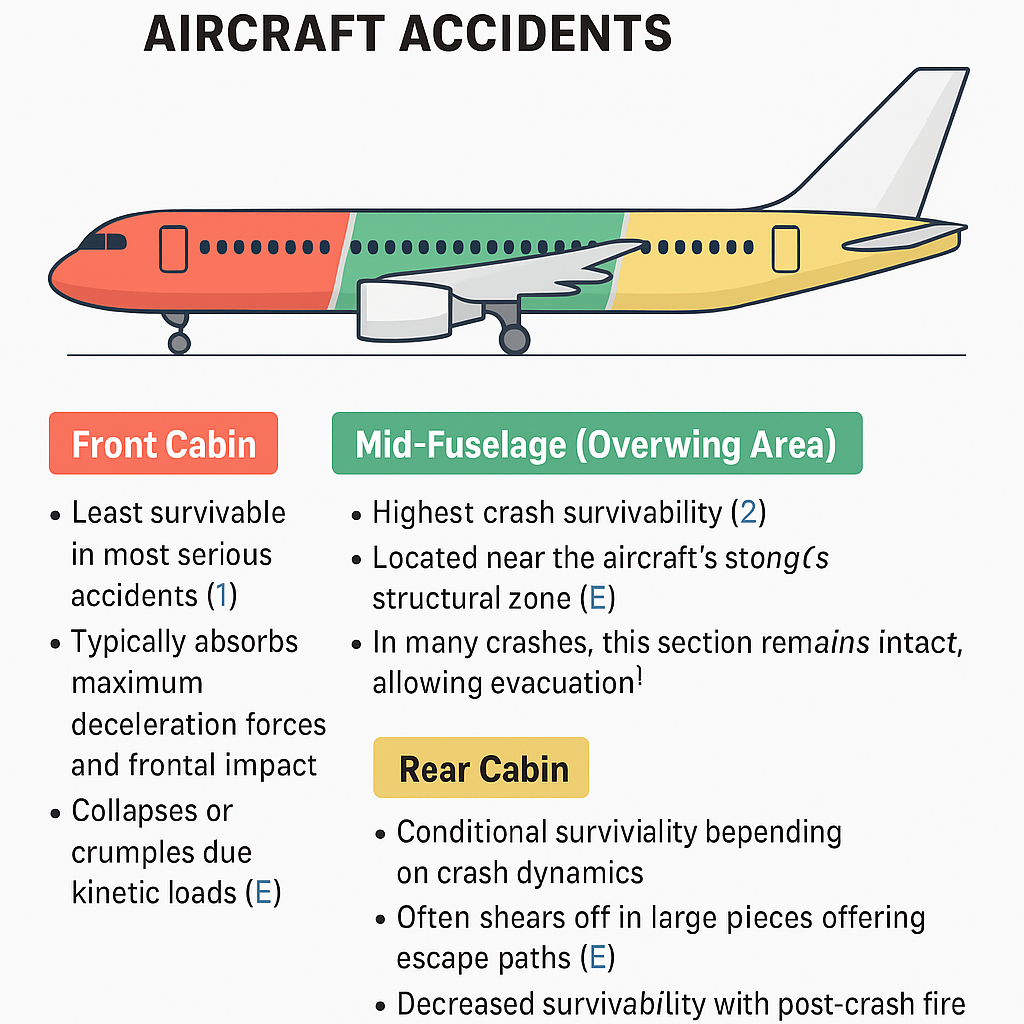

🟢 THE MOST SURVIVABLE SECTIONS OF AN AIRCRAFT

From historical crash data and Safety Science (2018):

| Section | Rows | Survivability | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-Fuselage | 9–20 | ✅ High | Over wing root, structurally strong, delayed fire exposure |

| Rear Section | 21–35 | ⚠️ Medium | Survivable on impact, but fire risk is high |

| Front Cabin | 1–8 | ❌ Low | Over-wing root, structurally strong, delayed fire exposure |

📌 Seat 11A, in mid-fuselage, had:

- Less vertical deceleration

- Structural integrity

- Short window for escape

🧾 STATISTICAL TRUTH: CRASHES ARE SURVIVABLE

Data from ICAO and NTSB shows:

- 86% of commercial aircraft crashes have survivors (Ekman, 2018)

- When excluding non-survivable crashes, the survival rate rises to 95%

- In IC605 (1990), 54 survived the impact, but many more died in the fire

“Public perception is flawed. Most people wrongly assume a crash equals death.”

— Fennel & Muir, 1992; NTSB, 2001

💡 THE 3-POINT BELT SOLUTION: WHY DON’T WE HAVE IT?

A simple 3-point seatbelt, used in every car since 1970, could have:

- Prevented internal injuries

- Kept passengers conscious

- Enabled them to self-evacuate

Already used in:

- Cockpits

- Business jets

- Military aircraft

But not economy cabins.

“There is no global regulatory mandate. And retrofitting costs money.”

— EASA, 2021; Chang & Yang, 2010

🧨 WHAT AI171 AND IC605 PROVE

IC605 – 1990, Bengaluru:

- 54 survived the impact

- Dozens perished in the fire

- Lap belts, blocked exits, and smoke were the causes

AI171 – 2025, Ahmedabad:

- One survivor

- Over 50 passengers in the mid-rear cabin could have survived

- Fire, 2-point belts, and inability to evacuate sealed their fate

“When the cabin fails, it’s physics. But when the seatbelt kills, it’s design failure.”

— Safety Matters Foundation (2025)

📢 CALL TO ACTION

We, at the Safety Matters Foundation, demand:

- ✅ Mandated 3-point seatbelts on all new aircraft

- ✅ Retrofitting in critical seat rows (9–35)

- ✅ Updated crashworthiness testing for fire and evacuation

- ✅ Passenger education on post-crash survival behaviour

📚 REFERENCES

- Ekman, S.K., & Debacker, M. (2018). Survivability in commercial aircraft accidents. Safety Science, 104.

- Grierson, D., & Jones, L. (2001). Principles of aircraft crashworthiness.

- NTSB. (2001). Survivability in Part 121 U.S. Air Carrier Accidents.

- Li, G., Baker, S. P., et al. (2008). FIA Score and Crash Injury Patterns.

- Tejada, J. (2005). Seatbelt syndrome in aviation.

- FAA AC 25.561. Crash impact design requirements.

- EASA. (2021). Cabin safety restraint systems – regulatory review.

- Fennel & Muir (1992). Public myths of aircraft crashes.

- Chang & Yang (2010). Study of the SQ006 crash evacuation patterns.

- SWL&DINMG., J. J., IlIamoox, A. H., SNYDIr. &. G.,and McFAwas, E. B.: Kinematic Behavior of The Human Body During Deceleration. CART Report 02-13, FAA, Oklahoma City, Okls., June 1962

🧾 FINAL WORD

The man in 11A didn’t just survive. He exposed the fatal flaw in our cabin safety system.

The miracle wasn’t divine — it was structural science. Everyone else who died — burned alive or incapacitated — died because their seatbelt failed them.

The question isn’t “Could we have saved them?”

It’s “Why haven’t we done it already?”

Discover more from Safety Matters Foundation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply